British Pantomime: Will Americans Love It, Too?

Pantomime is as much a part of Britain’s time-honored Christmas traditions as plum pudding, mince pies or the fairy atop the tree. In fact, it’s almost impossible to imagine an English Christmas without a performance of Cinderella, Puss in Boots or Jack and the Beanstalk going on in theaters throughout the commonwealth.

Without exception, from the West End of London to remote regional towns, people of all ages go the theater to slip back for a few hours into the magic of childhood. They hiss and boo at a giant, clap for Tinkerbell and join in the chorus of current songs.

This curiously simplistic form of entertainment has survived for some three centuries by young and old alike—in spite of being panned by theater critics as a plebeian pastiche of fairy tales, slapstick and buffoonery.

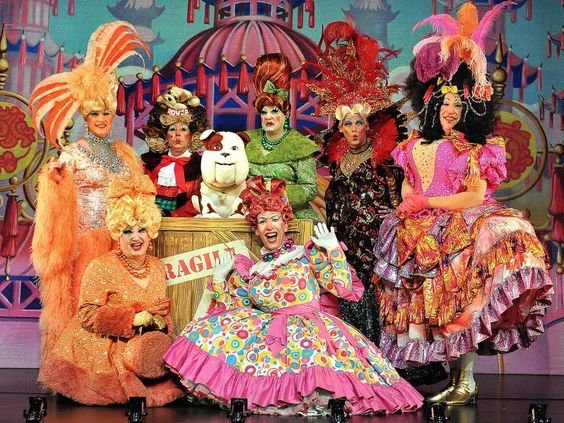

Essentially pantomime—familiarly known as “panto,” is not mime, but is based on the dramatization of a fairy tale or nursery story. The main characters frequently include a good fairy and/or a wicked stepmother, and the script is interspersed with buffoonery, topical jokes and slapstick.

How did this peculiarly English institution assume its current form? Why are so many of the female parts, including Widow Twinkey in Aladdin and the Ugly Stepsisters in Cinderella, played by men, while the hero, known as the Principal Boy, is invariably played by a beautiful young woman? Few in a panto audience would know the answers to these questions.

What they do know is that each year’s productions must incorporate the latest local and political jokes. In a Victorian-era version of Cinderella, the response to an ugly stepsister’s announcement that she was about to fit her foot into the crystal slipper was: “You couldn’t get your foot into the Crystal Palace”—a reference to the dazzling, monumental exhibition hall built in that period.

Despite the carping of theater critics, the humor in today’s pantomime still trends toward outrageous political or sexual innuendos about prominent figures (yes, even Donald Trump) and issues like the Common Market—and yes, even Brexit. So much for the critics! Even the smallest English child knows pantomime would not be pantomime without two actors dressed as a cow or horse, jolly old men in dresses and many funny, easy-to-understand jokes.

The London Times probably said it best back in 1923, when a reporter wrote: “Everybody pooh-poohs the pantomime, but everybody goes to see it. It is voted ‘sad nonsense’ and played every night for two months.”

There is no single reason for the enduring popularity of panto. Obviously, it is highly appealing to families with children, but one glance at a typical audience would reveal no particularly common characteristic. People enjoy panto for a variety of reasons and on different levels. Perhaps this is the secret of its survival.

According to Collier’s Encyclopedia, a dancing master, John Weaver, presented the first panto at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1702. The production, described as a “novel spectacle,” had a large cast of dancers, mimes, singers and actors and took the form of a spectacular ballet.

Though the name “pantomime” originally meant “a player of many parts,” this has changed over the years. When The Loves of Mars and Venus was presented at Drury lane in 1717, it was billed as a “dramatic new entertainment after the manner of ancient pantomime.”

Harlequin and Columbine than began to be introduced as central characters in plays borrowed from ancient myths. Such pantomimes were offered as a light touch after tragic or complicated dramas.

This changed dramatically in 1737 after a series of politically scorching satires had inflamed certain key members of Parliament. A licensing act was promptly passed requiring a copy of every play planned for public performance to be submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s office, along with the appropriate fee. This government office was then empowered to approve or disapprove the play or even to demand changes. In essence, a censorship law was put into place—and was not repealed until 1968!

The act also called for theaters to be licensed. An actor playing in an unapproved theater was deemed a “rogue or vagabond.” Covent Garden and Drury Lane became in effect the two official theaters. They were later joined by The Haymarket Theatre, which was granted a limited license in 1766. These theaters had the sole right to present legitimate drama.

Other theaters could exist, but were only allowed to present alternate forms of entertainment. It was in these theaters that music, dancing, Harlequinade and pantomime came into their own.

Thus panto began its gradual evolution. Transvestism became a characteristic feature. It became standard fare for the Principal Boy to be played by a young woman with shapely legs—a survival, perhaps, from the time when Shakespeare’s plots often required women to disguise themselves as men.

But it the Victorians to shape English pantomime into its present mold. Since its inception panto had always been a mixture of fantasy, low comedy, trick effects and spectacle, but in 1831, critics began to complain that Harlequin was being banished.

Ironically, the change was the result of pantomime’s incredible popularity. In their search for plays on which to base their spectacular effects, the Principal Boys and Widow Twankeys collected an extraordinary jumble of themes: Aladdin, Robinson Crusoe, Jack and the Beanstalk, Dick Whittington, Little Miss Muffet, Babes in Wood, Cinderella, Puss in Boots, Sindbad the Sailor and Mother Goose.

Toward the end of the century, the Harlequinade had virtually disappeared in the West End, and pantomime became almost entirely concerned with a loose, fairy-tale plot, trick effects and music-hall comedy.

Pantomime has demonstrated an amazing ability over the decades to reflect the manners and mores of its audiences. Yet, two elements remain strong and constant: the disapproval of theater critics who generally deride the vulgarity, over-simplicity and length of performances—and box office receipts, which invariably laugh in the critics’ faces and paint a picture of enduring success.

Will Americans Embrace Panto?

Some years ago, I saw a production of Jack and the Beanstalk in Ireland—and I laughed my head off. Yet I was aware of being surrounded by local people who had known and loved panto for years—and were having a grand time participating in the fun. So I wasn’t sure if Americans would embrace that very particular kind of fun at the theater.

A skeptical view was suggested in 2008 by Lorna Luft who was appearing as the Wicked Witch in a panto version of The Wizard of Oz in the city of Salford, U.K. In a piece she wrote for The Telegraph, she said: “You could never transport panto to the US, it just wouldn’t work. Men dressing up as women wouldn’t go down well in Middle America.”

Yet when I consulted Wikipedia, I found to my great surprise, that according to Professor Russell A. Peck of the University of Rochester, there had been several panto productions of Cinderella in the US as early as 1808, and that a production of Humpty Dumpty at the Olympic Theatre in New York City had run for at least 943 performances between 1868 and 1873. (One estimate put the number at 1,200, which would make it the longest-running pantomime in history!)

Since then a number of panto productions have slid into the US, generally without great fanfare. In 1993, Zsa Zsa Gabor starred in a production of Cinderella at the UCLA Freud Theatre. Starting in 1996, a group of four British ex-pats known as Theatre Britain, put on a number of shows in North Texas. Stages Repertory Theatre in Houston, Texas, has presented pantomime-style musicals during the Christmas holiday season since 2008. Lythgoe Family Productions produced pantomimes since 2010 in California, and more recently in Texas.

For the past 14 years, the People’s Light and Theatre Company in Malvern, Pennsylvania, has presented pantomime productions. This year, Little Red Riding Hood will debut during the holiday season.

During my research, I hoped to find a production in New York City. (The Abrons Arts Center on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, had offered pantos for a couple of years, but I had missed those.)

I found a group called The OPTimistiks on the crowd-funding site, Indiegogo, trying to raise money for a production of Dick Whittington. As of this writing, they seemed to be halfway to their goal: a show lovingly set in New York, where the title character (yes, played by a girl) comes to the Big Apple to seek fame and fortune on Simon Trouser’s P-Factor talent contest. Standing in his way: bungling Mayor Gloomberg and scheming Sara Pain, with Lady Goo-Goo (played by a guy) on his side.

I would love to see that show. Wouldn’t you?