The Society Queen Who Dethroned Prohibition

Pauline Sabin, the Society Queen who Dethroned Prohibition

Throughout history, speeches have been made that served to inspire and stir audiences. In Shakespeare’s play, Augustus inspires listeners to take vengeance on Julius Caesar’s assassins. In England, in 1940, Churchill’s speech, “We shall never surrender,” rallied the British people from seeming defeat by Nazi Germany.

In the U.S., on March 4, 1929, a similar emotional reaction occurred, but in the opposite way. In a select audience in Washington, D.C., Pauline Sabin, wealthy socialite and member of the Republican Party National Committee, waited hopefully for the speech of the new President, Herbert Hoover. Sabin had initially supported Prohibition, thinking it would brighten everyone’s lives. In those days, the terms “Wets” and “Dries” were fighting words, and Sabin still considered herself a “Dry.” But, throughout the 1920s, she had seen Prohibition’s miserable failures, breakdown of law and respect for law, and an epidemic of criminal behavior. She was gradually turning into a “Wet.”

Sabin had supported Hoover in the 1928 Presidential campaign. Although he previously had made some anti-liquor remarks, she thought that he couldn’t be a thoroughgoing Prohibitionist—after all, he was much more worldly and educated than his two predecessors, Harding and Coolidge. But Hoover’s speech soon erased her optimism.

Everyone has said that Hoover was a terrible speaker. But his remarks on Prohibition were worse. He criticized states for not enforcing Volstead and related laws vigorously. He went further by castigating individual citizens for not only associating with criminals and bootleggers, but for looking the “other way” when Prohibition laws were being violated. For Sabin, this was the last straw.

The next day, she resigned from the Republican National Committee. With other society matron friends, they formed what was at first an ad hoc group to look into combatting Prohibition. Eventually, due in part to Sabin’s nationwide organizing, the little group grew to include women from all walks of life and ethnic backgrounds. The official name for the group came to be “Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform “(WONPR). To avoid turning off potential members initially, they used the word “Reform”, but Sabin and her 11 original founding friends were determined to achieve complete repeal.

Sabin’s strategy was similar in many ways to those of the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), called the most powerful lobbying group the U.S. had ever seen. Her approaches were similar to those of the late Wayne Wheeler, an unimpressive-appearing Kansas lawyer, but a brilliant tactician and relentless campaigner for the prohibitionist goals of ASL:

- Emphasis on one issue, Prohibition repeal, in this way, designed to appeal to both Republicans and Democrats.

- In the 1930s, when the Depression really hit home, emphasis on jobs that would be created by resurrection of the liquor industry, which had been fifth largest in the country; AND generation of badly needed tax revenues for governments.

- Appeal to mothers about the dangers to their children from prevailing lawlessness and outright contempt for the law.

- Appeal to mothers over what was happening to their daughters—when saloons were legal, respectable women were usually afraid to enter, due to social stigmas; now, they openly drank with men and openly entered known speakeasies, with boyfriends or even alone.

- The ASL had advocated women’s suffrage as a source of support. Now, WONPR counted on women’s voting power to help the repeal cause. Also, Sabin’s leadership, clearly showing her society, superbly dressed credentials, seemed to inspire women from the middle and even lower economic classes, instead of repelling them.

- Well organized letter writing and telegramming campaigns to influence elections at both federal and state levels.

- Although WONPR didn’t stress the point, they would admit, if pressed, that states and local areas should be permitted to remain dry, if they desired.

One factor from the 1928 Republican (and “Dry”) landslide undoubtedly fed Sabin’s disgust. The victors interpreted their victory as a mandate for a much tougher campaign to enforce Prohibition. They forgot that bigotry against Catholic Al Smith and apparent nationwide prosperity had been even bigger factors than “Dry” sentiment. The Jones Act changed many violations of Prohibition laws from misdemeanors to felonies with minimum prison sentences. Also, the enforcement budget for federal agents was increased. But this led to widespread resentment over what is called today “Federal overreach”, even from those inclined to call themselves “Dries.”

Hoover continued to refer to Prohibition as a “noble experiment.” His Wickersham Commission, charged with a thorough investigation of the Volstead Act, seemed to recommend leaving things just as they were. Together with widespread unemployment, bank failures, and stock market collapse in 1929 and later, the campaign of Sabin’s WONPR led to Democratic recapture of Congress in the 1930 elections. Then, her group contributed to Franklin Roosevelt’s landslide victory in 1932 with its endorsement.

But the enormity of what Sabin helped accomplish shouldn’t be measured just by a Presidential endorsement. When the 18th Constitutional Amendment was completely ratified on January 16, 1919, its enforcement date was designated as one year later in 1920. In one celebration of ASL, on January 16, 1920, a spokesman said, “At one minute past midnight…a new nation will be born.” One implication of that boast was that it was considered impossible to repeal a Constitutional amendment. After all, it took 2/3 of Congress and ¾ of the states to ratify it, and the same super majorities would be required for repeal.

One eventual aid to repeal had occurred in 1929. Congress had apparently neglected its legally required duty to reflect current census figures in apportioning Congressional districts. This led to greater representation from urban districts, who would eventually reflect “Wet” sentiments over rural areas that would tend to be “Dry.”

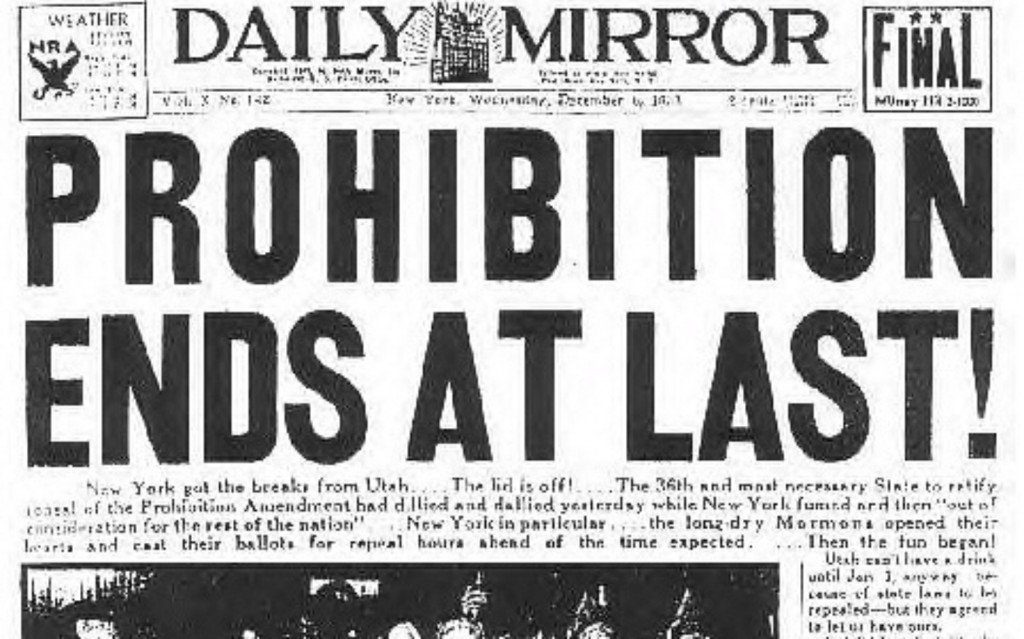

In February, 1933, the amendment to repeal Prohibition, the 21st amendment, first came before Congress. On February 14 and 16, despite one brief attempt at a filibuster, both Houses of Congress had voted for repeal by the required 2/3. Shortly after, when Roosevelt took office, the Volstead Act was drastically reformed, but made it clear that states and local areas could still stay dry.

Now, the state process, formerly considered hopeless, began in earnest. By midsummer, 1933, 15 states had ratified the amendment. Even supposed dry bastions like Arkansas, Alabama and Tennessee voted to ratify. Finally, on December 5, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the 18th amendment. The Prohibition era, which had ended with what one author termed “Tommy guns and Hard Times,” was over.

Pauline Sabin and leaders of WONPR marked the occasion with dinner at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C. No liquor was served, but they knew full well what they had accomplished over the prior four plus years.

In a superb book, Last Call, Daniel Okrent describes all the events and campaigns in both the 19th and 20th centuries that led to the 18th amendment and then, 13 years later, to its downfall with the 21st amendment. But for me, the most inspiring part of the book is his description of the stately society queen who, when completely turned off by a miserable speech, was inspired to work for something positive that brightens our lives today.