History comes alive in Lexington and Concord

It’s hard to separate the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concord, as their shared past forever links them. History was made here on April 19, 1775, when the colonial militia and minutemen, determined to protect and defend their homes and farms, challenged the British Redcoats, called “Regulars.” Their efforts led to a series of skirmishes, known as the Battles of Lexington and Concord. These battles ignited the start of the American Revolution, a war that lasted for seven years; the outcome of which we all know was political independence and the formation of the USA.

When visiting these towns, begin your journey through history at the Lexington Visitors Center, where a diorama of the Battle of Lexington is on display with accompanying information. After clearing some of those historical cobwebs from your mind, purchase a ticket for the Liberty Ride, a guided trolley tour. You’ll see significant historical sites and hear stories of witnesses to the first day of the American Revolution.

Your guide will give you a crash course on what led up to the events of that fateful April day. And they will reiterate the many issues between England and the colonies that created the conflict. I, for one, needed this refresher course, as it had been a lifetime ago since I had studied this period in history.

Buckman Tavern in Lexington. Photo by Debbie Stone

Diorama depicting Battle of Lexington inside Lexington Visitor Center. Photo by Debbie Stone

Lexington Minute Man. Photo by Debbie Stone

To recap: England was strapped for cash after winning the war with France, so they looked to the colonies for money by levying taxes on necessary products. The colonists became angry about the taxes and started to push back by boycotting British goods and intimidating the tax collectors. These colonists were identified as Patriots, as they rebelled against British rule and advocated for independence. Those that sided with England were called Loyalists.

The events of the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party fueled the Patriots’ fire, causing them to stockpile munitions in Concord. Major General Thomas Gage, the commander-in-chief of British forces and Governor of Massachusetts Bay at that time, sent 800 Regulars to Concord to seize and destroy the munitions in anticipation of a rebellion.

News got out about this mass incursion of troops through a spy network established by the Patriots. This is when Paul Revere and others set out on that famed horseback ride through the countryside to warn of the approaching Regulars. And contrary to what we’ve all learned is that Paul most certainly did not shout “The British are coming!” on his ride. He would have most likely said, “The Regulars are coming!” That’s because everyone was British at that time.

The Regulars met the militia and minutemen, at the Common in Lexington. The Regulars were told to stand their ground and not fire unless fired upon, while the militia and minutemen were eventually ordered to disperse. However, as most of them were leaving and had their backs to the Regulars, a shot rang out from an unknown source. To many, this became known as the first shot of the American Revolution.

The Regulars began firing without orders, despite being told to cease. When the dust settled, eight militiamen were killed and ten had been wounded, while there were no fatalities on the Regular side.

Churches in Concord often served as platforms for abolitionist speakers. Photo by Debbie Stone

Emerson House. Photo courtesy of Visit Concord

Freedom’s Silhouette. Photo courtesy of Visit Concord

As you hear this story, you’ll ride by the Common, now known as the Lexington Battle Green. Make sure to return and explore this place on your own or via a guided walking tour, as there’s much to see.

The Battle Green is now a park and memorial to the events of April 19,1975. Here’s where you’ll find “Lexington Minuteman,” the life-size bronze figure of a colonial farmer carrying his musket. Sculpted by Henry Hudson Kitson, the figure was originally meant to represent the common minuteman, but it has now become accepted as the image of Captain John Parker. Parker was the military officer who commanded the minutemen at the Battle of Lexington.

Nearby is a plaque marking the site of the old wooden belfry, which stood on the green and once summoned the militia to the area. You’ll also see two monuments that mark the approximate position of the line formed by the minutemen that day. And you can’t miss the Revolutionary War Monument, a granite obelisk honoring the men who died on the Green, seven of whom are interred in the tomb beneath the monument.

Across the street is Buckman Tavern, one of the few colonial era buildings still standing around the Battle Green. It served as the gathering place of the Lexington militia and minutemen before the British attack. Today, it’s a museum, where you can take a self-guided audio tour and peruse the many items and artifacts dating back to 1775. There’s a kitchen, small and large parlors and the taproom. Look for the old front door with its bullet hole made by a British musket ball during the battle.

Wright Tavern. Photo by Debbie Stone

Concord Museum. Photo by Debbie Stone

Map of Concord’s historical sites. Photo by Debbie Stone

Near the tavern is the Minutemen Memorial, created by artist Bashka Paeff. Set on a granite base, it depicts six minutemen posed in various stances as they fight at the Battle of Lexington. And on the lawn of the Visitor Center is another monument entitled “Something Is Being Done,” by sculptor Meredith Bergmann. This bronze piece honors and celebrates the contribution of Lexington women to the town’s “political, intellectual, social and cultural history.”

Other historic homes of note in Lexington include the Hancock-Clarke House and Munroe Tavern. The former is where John Hancock and Samuel Adams, prominent leaders in the colonial cause, were guests of the Reverend Jones Clark. On Paul Revere’s midnight ride, he made a beeline for this house to warn these men that British troops were coming to arrest them. The Munroe Tavern, on the other hand, was the temporary headquarters for British General Earl Percy, another figure in the Revolutionary War.

The trolley also takes you near the North Bridge within the Minute Man National Historical Park in Concord. This is the location of another significant skirmish. Militia and minutemen from Concord and surrounding towns exchanged gunfire with the Regulars at this critical river crossing. Though the fighting lasted mere moments, it marked the start of a massive battle that ensued over sixteen miles, as the British retreated.

Exhibit inside Lexington Visitor Center. Photo by Debbie Stone

Lexington Minutemen Memorial. Photo by Debbie Stone

Lexington’s Battle Green in resplendent fall color. Photo by Debbie Stone

You might think you’re seeing things, as there’s another Minute Man statue here. This bronze, by Daniel Chester French, is set near the spot where the first militia men were killed in Concord. It represents the citizen soldier of 1775 and depicts a minuteman stepping away from his plow to join the patriot forces at the Battle of Concord. This iconic image is today the symbol of the National Guard, and over the years, it has also been used on coins, postage stamps, corporate logos and savings and war bonds.

Inscribed on the front facing of the statue is the first stanza of the poem “The Concord Hymn” by Ralph Waldo Emerson, in which he famously described the first shot of the Battle of Concord as the “shot heard ‘round the world.”

Depending on who you speak to and what you might read, this “shot” took place at either the Battle of Lexington or the Battle of Concord, where the militia and minutemen were given the first order to fire upon the Regulars.

Exhibits inside North Bridge Visitor Center. Photo by Debbie Stone

Exhibit on the Indigenous People of Concord in the Concord Museum. Photo by Debbie Stone

Emerson’s study in the Concord Museum. Photo by Debbie Stone

The park is another good place to return to, as there’s a visitor center with exhibits, several historic homes and plenty of monuments. Get your steps in or cycle your way along the park’s Battle Road Trail. Much of it follows the original remnants of the Battle Road where thousands of colonial militia and British Regulars fought. Take note of the site where Paul Revere was captured by a British patrol – a fact I didn’t know. Truth is, Revere actually never made it to Concord, though another rider, Samuel Prescott, did. And yet, Paul Revere gets all the credit! He became an American folk hero, courtesy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

After you’ve explored Lexington, shift your full attention to Concord. Start at the Concord Visitor Center and check out the walking tours offered or request a private tour. There’s quite a variety of tours and depending on your interests, you can delve further into the American Revolution, learn about Concord’s connection to the Civil War and/or discover the different groups of people who lived here, the contributions they made and the roles they played in history. These include indigenous people, women, African Americans, authors and more, all who left their indelible marks on the fabric of society.

I opted for a private tour, as I wanted to touch upon a number of themes. My guide, Joe Palumbo proved to be a font of knowledge on all things Concord. He knew just how much information to dispense and never lectured, but rather spoke in a conversational tone, encouraging much back and forth discussion.

Something is Being Done Monument in Lexington. Photo by Debbie Stone

Revolutionary War Monument on the Battle Green in Lexington. Photo by Debbie Stone

You can take a guided walking tour of Lexington’s Battle Green. Photo by Debbie Stone

Joe began the tour with some information about Concord’s indigenous people. He explained that for over 10,000 years, the Nipmuc and Massachusetts peoples called this area Musketaquid, meaning “the land between the grassy rivers.” They found this location desirable, as the hunting and fishing were good and the waterways also provided a transportation network. But cultures collided once European fur traders and later English settlers arrived. Today, there are more than 15,000 indigenous people living in Massachusetts.

We then headed to the center of town to visit notable sights dealing with different aspects of history. The Civil War Monument, honoring those who served the nation during this war, opened up a discussion on how Concord viewed the issue of slavery. Joe said that for years, the townspeople gave no thought to this issue. However, this changed when a group of prominent women formed the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society.

Founding members included Lidian Emerson, wife of Ralph Waldo Emerson and her daughter Ellen; Mary Merric Brooks, the society’s primary organizer; Cynthia Dunbar Thoreau, mother of Henry David Thoreau, and her two daughters, Helen and Sophia; Abigail Alcott, mother of Louisa May; Susan Garrison, resident of Concord’s Robbins House and the sole woman of color; and Lucy Brown.

Take the Liberty Ride trolley tour in Lexington. Photo by Debbie Stone

The society hosted noted abolitionist speakers and they held events to raise money for the antislavery cause, attended anti-slavery conventions, disseminated anti-slavery publications and basically served as “the foot soldiers of reform.” They, more than the men in town, took it upon themselves to try and right these societal wrongs, and helped make Concord famous for its liberal leanings.

Joe directed our attention to the First Parish Church, as well as the First Universalist Church, both of which offered a platform for antislavery speakers. As I gazed at these buildings, I imagined what the scene would be like back then with the likes of Frederick Douglas, Harriet Tubman and John Brown gave their fiery addresses.

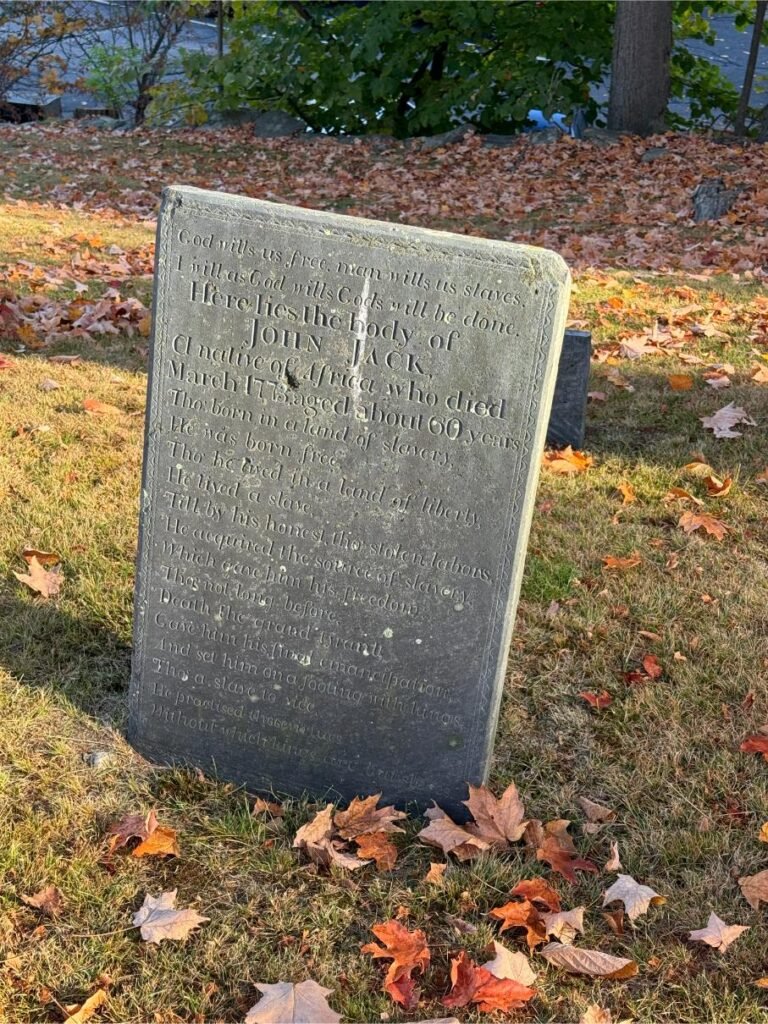

Overlooking the town center is the Hill Burying Ground, the earliest European burial site in Concord. Joe stopped at one grave in particular, that of John Jack, and proceeded to tell us his story. John was born free in Africa, but enslaved in Colonial New England. He bought his own freedom over the course of many years, but he was unable to convince the citizens of Concord to honor his “full humanity.” John has the distinction of being the first free black landowner in Concord, as well as the distinction of being one of only three freed black men with a headstone in the U.S.

At the time of the American Revolution, forty out of the 2,000 people living in Concord were enslaved. Joe further noted that four to five thousand enslaved men fought on the patriots’ side, while seven to nine thousand fought for the British for the promise of emancipation.

Louisa May Alcott’s gravestone. Photo by Debbie Stone

John Jack’s headstone. Photo by Debbie Stone

Thoreau’s gravestone. Photo by Debbie Stone

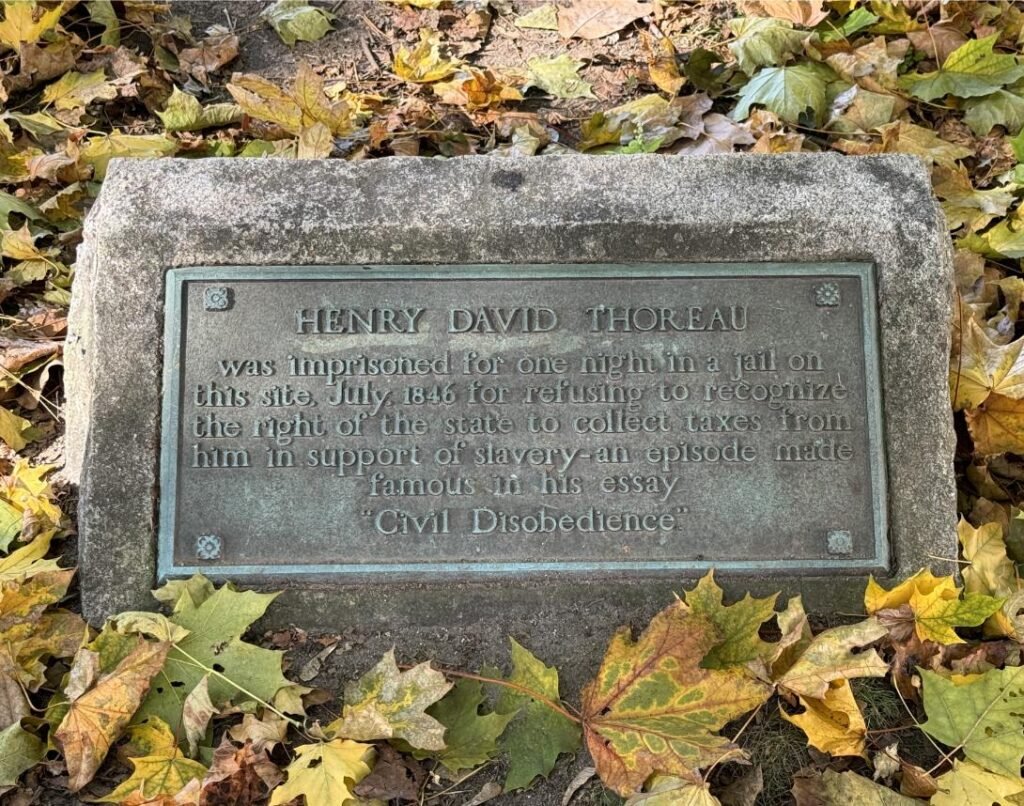

Other notable sites in the town center include the Concord Town House, circa 1851, which became the center for the community; the Old Jail Site, indicating the place where Thoreau spent a night to protest the expansion of enslavement, leading him to write the essay, “Civil Disobedience,” and Wright Tavern, where a number of key revolutionary events took place, most notably the meeting of the First Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

If you go inside the tavern, which is now a National Historic Landmark, you’ll see some historic information displayed on the walls. Of interest to me was a description of colonial taverns in America and another featuring women who helped defend Concord on April 19, 1775.

Taverns were all-purpose establishments. They were used as meeting places for assemblies and courts, destinations for food, drink and entertainment, and most importantly, democratic venues of debate and discussion.

Site of Old Jail where Thoreau was imprisoned. Photo by Debbie Stone

Old Hill Burying Ground. Photo by Debbie Stone

The Wayside. Photo courtesy of Visit Concord.

Regarding the women and their actions on that pivotal April day, story has it that when the able-bodied males left town for the hills to prepare for battle, the only ones remaining were women, children and older men. The British Regulars arrived and had orders to search the homes to seize and destroy any weapons or supplies. Their mission failed, however, due to the cleverness and cunning of the women, who hid munitions and told a few tales to prevent the Regulars from accessing certain spaces in their houses.

Concord’s newest attraction, also in the town center, is an acrylic art installation called, “Freedom’s Silhouette.” Created by Liz Helfer, it depicts two 19th century Concordians, Ellen Garrison and Thoreau. The pair sit across from one another, each anchored to a park bench. You can sit next to them, as I did, and ponder their contributions to history.

Thoreau, who is known to most, needs little introduction. He was a leading transcendentalist (embracing idealism, focusing on nature and opposing materialism) and advocate of civil liberties. What you might not realize is how deep his fervor went in regards to anti slavery. He served as a conductor in the Underground Railroad, gave lectures attacking the Fugitive Slave Law and supported radical abolitionist militia leader John Brown and his party.

One hundred years before Rosa Parks, there was Ellen Garrison, daughter of Susan Garrison, a charter member of the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society. Ellen followed in her mother’s footsteps as an antislavery activist and taught freedmen and women post-Civil War. In 1866, she tested the nation’s first Civil Rights Act in court after sitting in a segregating waiting room in a Baltimore train station and being forcibly ejected. Ellen brought suit against the railroad station train officer who assaulted her, but a grand jury dismissed the case.

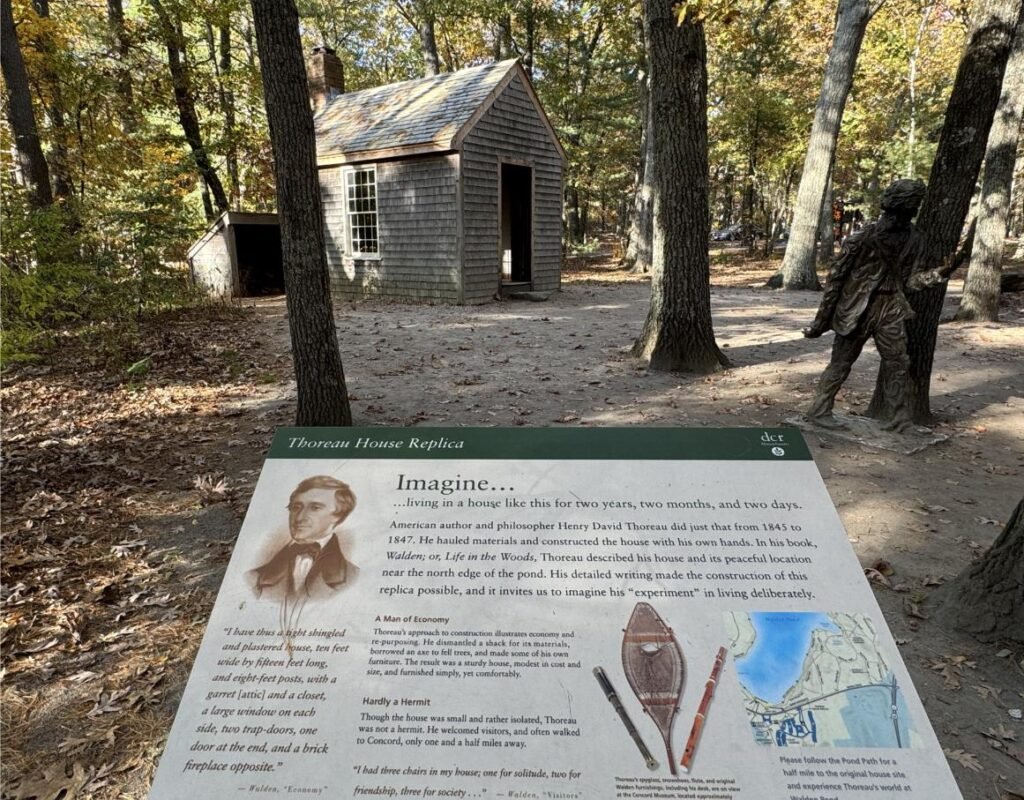

Thoreau cabin replica. Photo by Debbie Stone

Thoreau’s desk in the Concord Museum. Photo by Debbie Stone

For more on the Robbins family, visit the Robbins House. A rustic, two-family farmhouse, its occupants included Caesar, Ellen’s grandfather, Peter (Caesar’s son), Susan, Caesar’s daughter and her husband Jack Garrison, and Ellen, Caesar’s granddaughter.

Another of Concord’s interesting links to the past is its literary connection. Famed authors Louisa May Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Ralph Waldo Emerson all lived here at one time or another. You can tour their former homes, including the Ralph Waldo Emerson House, Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House, The Old Manse, The Wayside and the Thoreau Farm and Birth House.

The Orchard House is where Alcott penned “Little Women,” while Emerson’s first draft of his famous essay, “Nature,” was written at The Old Manse. Hawthorne was also a resident of The Old Manse, who rented the place and lived there with his wife Sophia. As for The Wayside, both the Alcott and Hawthorne families owned the house at different times.

Those interested in Thoreau can visit the Farm and Birth House, and then head to Walden Pond. The pond, or what I would label a lake, is where the author went to in efforts to live a simpler life. He built a small cabin in the woods and stayed there for two years, two months and two weeks, beginning in 1845.

During his stay, Thoreau kept a journal chronicling what he witnessed and learned from nature. His experiences provided the material for his book, “Walden.” His writings inspired an awareness and respect for nature. Because of his legacy, Walden Pond, which was designated a National Historic Landmark, is considered the birthplace of the modern conservation movement.

Now owned and managed by the MA Department of Conservation and Recreation, Walden Pond receives over half a million visitors annually. They come to see a replica of the cabin, hike the trails around the pond and in the woods, and take in the peaceful ambiance of the place. In fall, when I visited, the scenery was resplendent with autumn colors.

Another literary-oriented site is Authors Ridge in Concord’s Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. For many, this is a place of pilgrimage. People come from all over to pay their respects to these great literary minds. They often leave behind mementos such as pencils, pens and hand-written notes. At Thoreau’s gravesite, you’ll find pine cones, acorns and other elements of nature.

The Concord Museum should be on your list, too. Its collection of artifacts is excellent, especially those used on the day the American Revolution began. There’s everything from muskets, flints and powder horns to one of the two lanterns that Paul Revere put in the steeple of Boston’s Old North Church to signal the patriots of the advance of the Regulars. Other artifacts include Native American stone tools, Thoreau’s desk, furnishings from Emerson’s study and numerous decorative arts pieces.

One of the most dynamic and impactful exhibits is the multimedia presentation of the day the “shot heard ‘round the world” was fired. It’s done as an innovative timeline, using an 18th century map of the area. You see the events of 24 hours of history told in six dramatic minutes.

Feature Photo North Bridge. Photo by Debbie Stone

![French Artist Lucas Beaufort [INTERVIEW]](https://luxebeatmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2-W-Koh-Samui-440x264.jpg)