Last Tango in Paris: Napoléon’s Tomb

“Death is nothing, but to live defeated and inglorious is to die daily.”~ Napoléon Bonaparte

“That was the greatest and finest moment of my life!” a smallish man in a white raincoat proclaimed loudly as he exited the domed church at the Hotel des Invalides in Paris. Moments before, this man stood trembling with excitement and removed his cap out of respect as he gazed for a long time at an ornate marble tomb. It was June 23rd, 1940; just three days after the French capital had become German-occupied territory. The following day during his official sightseeing city tour, Adolf Hitler made a second visit to the Église du Dôme with his sycophant generals to again pay homage to his military idol, Napoléon Bonaparte I. Hitler was so moved by his visit that in tribute to the French emperor, he decreed that Napoléon’s son’s coffin be moved from Vienna to lie beside his father.

Napoléon and Hitler

Napoleon’s shadow looms large over the museum of the Army of France. The museum contains 500,000 objects, including weapons, armor, artillery, uniforms, emblems and paintings dating from antiquity to the present day.

During his brief visit to Paris, Hitler considered Napoléon’s tomb to be a must-see attraction. History has drawn several comparisons between Napoléon and Hitler. Both men were deemed to be foreigners in the countries they ruled, with Napoléon being born in Corsica just one year before it became a part of France, while Hitler was born in Austria, and moved to Munich in 1913 where he denounced his Austrian citizenship. The armies lead by both men invaded Russia while plans were being developed to invade England. Among other coincidences, both men were under 5 feet 9 inches tall. On April 30, 1945, one of these men unceremoniously committed suicide inside his Führerbunker in Berlin, whereas on May 5th 1821, the other died on the remote volcanic island of Saint Helena where he had been living in exile since 1815.

“This Cursed Rock”

Red marks the spot for the island of Saint Helena

After his defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, Napoléon fled to Paris. Having fallen out of favor with France’s military establishment, he was forced to abdicate his throne on April 6, 1814 and went into exile on the Mediterranean isle of Elba. In March 1815, Napoléon escaped from Elba and quickly made his way back to Paris where he triumphantly reclaimed the throne of France. European allies responded by forming a Seventh Coalition which defeated Napoléon at the infamous Battle of Waterloo in Belgium on June 18, 1815. Fearing a repetition of Napoléon’s previous return from incarceration, the British government exiled him to Saint Helena, a British overseas territory, and one of the most remote tropical islands in the world. Situated in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,200 miles from the nearest point of land, this was a place from which it was thought the former emperor could never escape. Napoléon called his rugged island prison, “this cursed rock.”

Death in Exile

“My death is premature. I have been assassinated by the English oligopoly and their hired murderer.” ~ Napoléon Bonaparte (as stated in his last Will and Testament)

Public Domain – Napoleon crossing the alps by Jacques-Louis David

On May 5, 1821, Napoléon Bonaparte I died in exile on Saint Helena. While it was initially believed his cause of death was due to stomach cancer, conspiracy theorist believe he was murdered and died from arsenic poisoning. One month earlier, Napoléon had requested in his last will and testament that his body be buried “on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people whom I loved so well.” While Bonaparte did not believe his body would be left on Saint Helena, he requested that if his body were to remain on the island, he wanted to be buried near the fountain which had provided him with water during his sojourn on the rock. Napoléon’s request was honored and his body was buried on May 9th at Saint Helena’s Geranium Valley, near a spring of cool water, at the foot of some weeping willows.

Only a few blocks away from Napoleon’s Tomb École Militaire, the military school where the future Emperor was commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant of Artillery in September 1775

Bonaparte’s grave was approximately 10-feet deep, lined with bricks, and the interior of the tomb was made from slabs of stone. After his casket was lowered by means of pulleys, the tomb was sealed with a large stone, and then topped with a layering of bricks, cement, clay and stones. Napoléon’s body remained here undisturbed for 19 years until October 15, 1840.

“Retour des cendres” (Return of the remains)

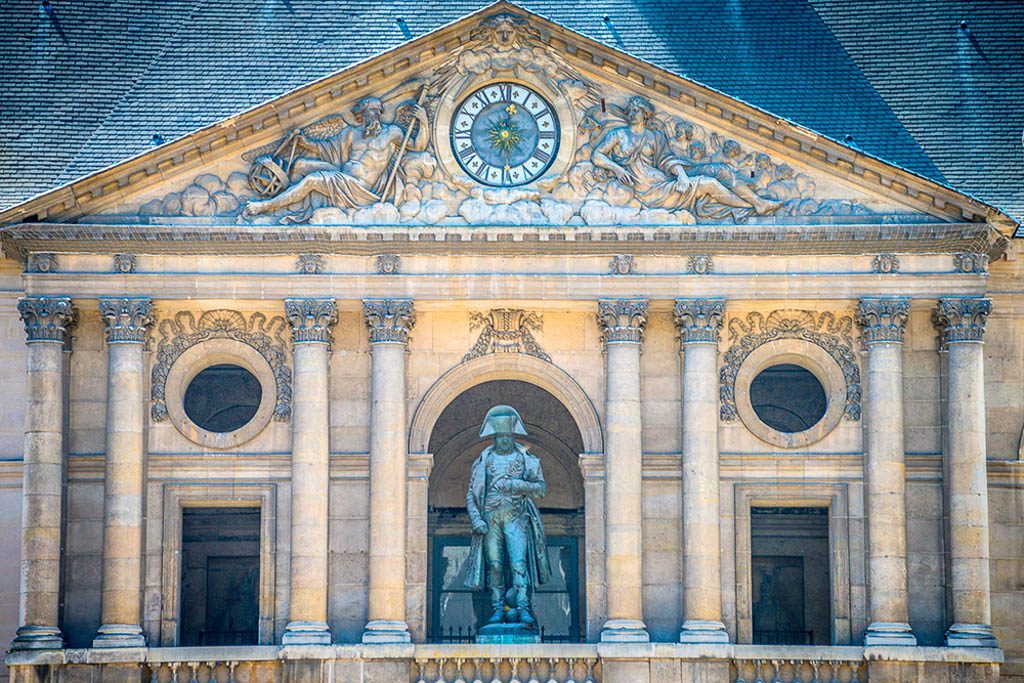

The Army Museum at Les Invalides was originally built by Louis XIV as a hospital and home for disabled soldiers

Back in France, there was no desire amongst officials to have Napoléon’s remains returned as nobody wanted to revive Bonapartist-mania. That is until 1840 when historian Adolphe Thiers, who was serving as French prime minister and foreign minister, beseeched a reluctant King Louis Philippe I to repatriate Napoléon’s remains. Thiers regarded the “retour des cendres” as an opportunity unite the French people and boost the government’s popularity. On October 8, 1840, the frigate La Belle Poule, painted black and escorted by the corvette Favorite, arrived at Saint Helena. King Philippe’s son, the Prince of Joinville, led this expedition which included both dignitaries and a number of people who had all known Napoléon during his incarceration on Saint Helena.

Inner courtyard at the Army Museum at Les Invalides

In the presence of those who witnessed his burial, Napoléon’s grave was opened on October 16th after excavators had worked throughout the previous night to break through the grave’s multi-layers of stone, cement and brick. An official record of the coffin’s opening stated, “The cover of the third coffin having been removed, a tin ornament, slightly rusted, was seen, which was removed, and a white satin sheet was perceived, which was detached with the greatest precaution by the doctor, and Napoléon’s body was exposed to view. His features were so little changed that his face was recognized by those who had known him when alive. The different articles which had been deposited in the coffin were found exactly as they had been placed. The hands were singularly well preserved. The uniform, the orders, the hat, were very little changed. His entire person presented the appearance of one lately preserved. The body was not exposed to the external air longer than two minutes at most, which were necessary for the surgeon to take measures to prevent any alteration.”

After confirming Napoléon’s body was still there, the tin and wood caskets were closed, the lead casket was closed and re-soldered. Then all the were placed in a new lead casket, sent from Paris, which was also soldered shut. These were all placed inside a new ebony casket, which was locked and put in an oak case, to protect the ebony. The whole thing weighed 2,645 pounds.

A Triumphant Return

On October 18th, La Belle Poule set sail from Saint Helena with Napoléon’s mortal remains. After dropping anchor in the French harbor of Cherbourg on November 30th, his casket was transferred over land to Val-de-la-Haye, near Rouen, where it was loaded aboard the steamer La Dorade, to be ferried up the River Seine. On December 15, 1840, Napoléon’s body was transferred to a funeral carriage.

“It is not necessary to bury the truth. It is sufficient merely to delay it until nobody cares” ~ Napoléon Bonaparte

The Dôme des Invalides, which contains Napoleon I’s tomb, is the emblem of the Hôtel National des Invalides. Situated in Paris on the Esplanade des Invalides, within the 7th Arrondissement, this large church, built between 1679 and 1706 during the reign of Louis XIV, is famous for its magnificent dome, which is considered to be a typical example of baroque architecture. The dome’s ceiling is decorated by frescoes representing Saint Louis and Christ. The exterior of the dome was gilded in 1715

In celebration of Napoléon’s life, the French government organized an elaborate show to commemorate the late Emperor. Drawn by 16 black horses, the funeral carriage procession passed before a crowd estimated to be 750,000 strong. The funeral procession stopped briefly under the Arc de Triomphe, which was built on the orders of Napoléon in 1806, but was not completed until 1836. Napoléon’s funeral carriage then traveled down the Champs Elysees before crossing the Seine, to the Hotel des Invalide’s Chapelle Saint-Jérôme where a funeral service was held. Napoléon’s coffin remained on public display in Chapelle Saint-Jérôme for only twenty-four hours. It seems the French government wanted the Emperor to be remembered, mourned and celebrated, but just for only one glorious patriotic day. Napoléon’s body remained hidden from view in the Chapelle Saint-Jérôme for the next twenty-years until what was to become an ornate crypt was built.

The Tomb of Napoléon was designed by the architect Visconti (1791-1853). It is made from red porphyry with a green granite base and circled by a crown of laurels and inscriptions of the great victories of the Empire. The body of the Emperor was laid in the tomb on April 2nd 1861

Two Funerals for Napoléon

Known as the Temple de Mars during the French Revolution the Dome Church became a military pantheon during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte

“Let France have good mothers, and she will have good sons.” ~ Napoléon Bonaparte

Architect Louis Visconti designed Napoléon’s massive crypt in 1842. It took until 1861 for construction of this grand monument to be completed which beneath the dome features a fifteen-foot-tall deep red sarcophagus carved from aventurine quartzite (not red porphyry as is so often stated) and resting upon a green granite pedestal. Inside the large sarcophagus, Bonaparte’s remains are entombed by six progressively larger concentric coffins all nested inside the other and built from different materials, including mahogany, two others of lead, ebony, and oak and encircled by 12 marble victory statues mounted up against the pillars of the crypt. On the mosaic floor, a crown of laurels motif surrounds the sarcophagus, and on the mosaic floor are inscriptions referencing the great victories of the Empire. Beneath the golden vault of the Eglise du Dome Church lie the remains of the slight statured Corsican who became France’s greatest soldier. Napoléon Bonaparte I was finally laid to rest on April 2, 1861 when his body (still in all the caskets) was transferred to the new sarcophagus during a private ceremony overseen by Napoléon’s nephew, Emperor Napoléon III, his immediate family, senior government officials and dignitaries.

Napoleon’s Tomb in the crypt at Les Invalides

Beneath the Gilded Dome

“Glory is fleeting, but obscurity is forever.” Napoléon once said. Today, the biggest draw of the expansive Hotel des Invalides military complex is what lies within his massive custom-built ornate chamber. Napoléon’s enigmatic and complicated mystique looms as large in death as it did during his lifetime. His tomb is completely over the top, and something you must absolutely see with your own eyes. One can easily imagine that Napoléon’s ego would swell with pride if he knew his last resting place had become one of the biggest tourist attractions in La Ville Lumière.

In 1842, the architect Visconti had to redesign the church’s high altar to accommodate the Tomb

Until our next dispatch, dare to Explore…Dream…Discover.

Images for Sale

Do you like an image you see published by Jett and Kathryn Britnell? They are now available for purchase at their Britnell Photographics Photo Gallery.

Follow the link: Here