Explore canyons, dunes and ruins in Southwest Colorado

Hiking trails are typically an inherent part of most National Parks in our country. They offer opportunities for visitors to discover the highlights, as well as the lesser known features of each particular destination. It’s rare when a park doesn’t offer some type of trail system, but such anomalies do exist.

Great Sand Dunes National Park

Take Great Sand Dunes National Park, for example. This must-see wonder is one of Colorado’s most unique parks. Located in the San Luis Valley, the dunes were created hundreds of thousands of years ago after a large inland lake, which covered the valley, dried up. Over the years, a series of smaller bodies of water appeared and disappeared, leaving behind wetlands and an expanse of loose sand. Southwesterly winds picked up the sand and blew it toward a depressed bend in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, forming massive sand dunes.

Great Sand Dunes was first proclaimed a National Monument by President Hoover in 1932 and then between 2000 and 2004, it received National Park and Preserve status. Today, it continues to remain one of the Centennial State’s most beloved natural playgrounds.

The park protects the tallest dunes on the continent; the tallest of which is 755 feet above the valley floor at an elevation of 7,600 feet above sea level. Upon seeing these mountains of sand for the first time, visitors almost always comment on the bizarre quality of the scene. The 30-square-mile dune field appears as a Saharan-like landscape, an otherworldly spectacle.

This geological oddity, however, is not the only unusual aspect in the San Luis Valley. The valley itself is regarded as a paranormal hot spot. Believers around the world amass at privately owned watchtowers in hopes of spotting UFOs and extraterrestrial life. Also, the area is regarded as a mecca of spirituality that attracts numerous religious organizations. And then there are solar energy companies who use the valley to harness alpine-desert rays.

As for trails, you won’t find any at the park. There’s minimal signage and once you’re amid the dunes, footprints disappear quickly. You’ll blaze your own path and create your own adventure, whether you want to ascend High Dune, a 699-foot-tall behemoth, or up the ante and aim for famed Star Dune. The latter is the tallest dune, and only visible once you get to the top of High Dune. There’s a wonderful feeling of liberation as you forge your own way, free to go wherever you wish. And there’s plenty of room for social distancing at this park.

Make sure to wear sunscreen, bring plenty of water and have appropriate footwear. The latter is especially important as the temperature can reach a toasty 150 degrees on a sunny day and your bare tootsies will burn, baby burn! Take the opportunity either before or after your hike, or both, to cool off in Medano Creek, just past the visitor center and at the entrance to the dune field. Splash, wade or walk upstream/downstream as far as you like along this natural beach.

If you’ve ever climbed sand dunes, you know it can be tiring. With every step forward, the earth gives away and you slide two steps back. Surprisingly, the dunes at this park have a pretty firm surface, making them a bit easier to ascend, but know they are steep.

Sandboarding and sand sledding are also popular activities at the park. You’ll see every manner of sliding apparatus, from pieces of cardboard and cafeteria trays to snowboards and even skis. And you’ll definitely hear the riders’ unbridled joy, as they careen downhill.

Gunnison National Park

A few hours from Great Sand Dunes, is Colorado’s own Grand Canyon – the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. Here, you’ll encounter a very different, yet equally as dramatic, landscape. Carved through solid granite over billions of years, the canyon plunges an impressive 2,700 feet to the Gunnison River below. The gorge is deep, sheer and very narrow, which results in the sun’s rays only reaching parts of the bottom for a few minutes each day. Thus, the walls are often cloaked in shadows, making them appear black and forbidding.

Though it took countless millennia to form, the Black Canyon has only been a National Park since 1999. The park contains twelve miles of the 48-mile-long canyon and contains its deepest and most jaw-dropping section.

Visitors typically gain access to the park via its main entrance at the South Rim, a few miles outside the town of Montrose. The popular South Rim drive offers the best opportunity for views of this rugged grandeur. Overlooks are each designated and most necessitate a short walk along a trail leading from the pullout or parking lot.

Your first glimpse of the canyon is at Tomichi Point. The view is a tad disappointing as the canyon is not particularly steep at this juncture and the Gunnison River is not in view. Up next, however, is Gunnison Point, right behind the visitor center. Here, you’ll look northwards, across the canyon, which is now much narrower and grander than at Tomichi Point. Even more of the river is in view at Pulpit Rock Overlook. Cross Fissures follows, where a series of overlapping ridges and crevasses are on display.

Chasm View provides one of the most awe-inspiring overlooks in the park. You’ll be above the steepest part of the canyon, where the cliffs fall 1,840 feet over a horizontal distance of just 400 feet. You can then easily walk over to colorful Painted Wall, which has the distinction of being the highest cliff in Colorado. This visually stunning wall is made of Precambrian blue-black gneiss cut by pink pegmatite veins that run horizontally through the walls. You might spot an experienced climber or two here, or if you’re lucky, maybe even a Peregrine falcon as it jets across the canyon. It’s the fastest bird in the world and can exceed speeds of 200 miles per hour.

Sunset View marks the westernmost spot along the South Rim Road and allows a panorama of the downstream section, all the way to the Uncompahgre River Valley in the far distance. At High Point, take the Warner Point Nature Trail. Markers indicate various plants and trees, such as the prolific piñon pine and juniper. Along the way, you’ll pass through woodland and then down to a saddle, where you can glimpse bucolic green fields below and the town of Delta beyond. At the end of the trail, you’ll be rewarded with a picturesque view of the lower canyon and some of the river.

To see the canyon from the bottom up, take a drive along the East Portal Road. Go slow, as it’s a steep route with hairpin turns. Once you’ve reached the river, relax and enjoy a picnic amid the verdant and lush serenity. Or get your rod out and see what’s biting.

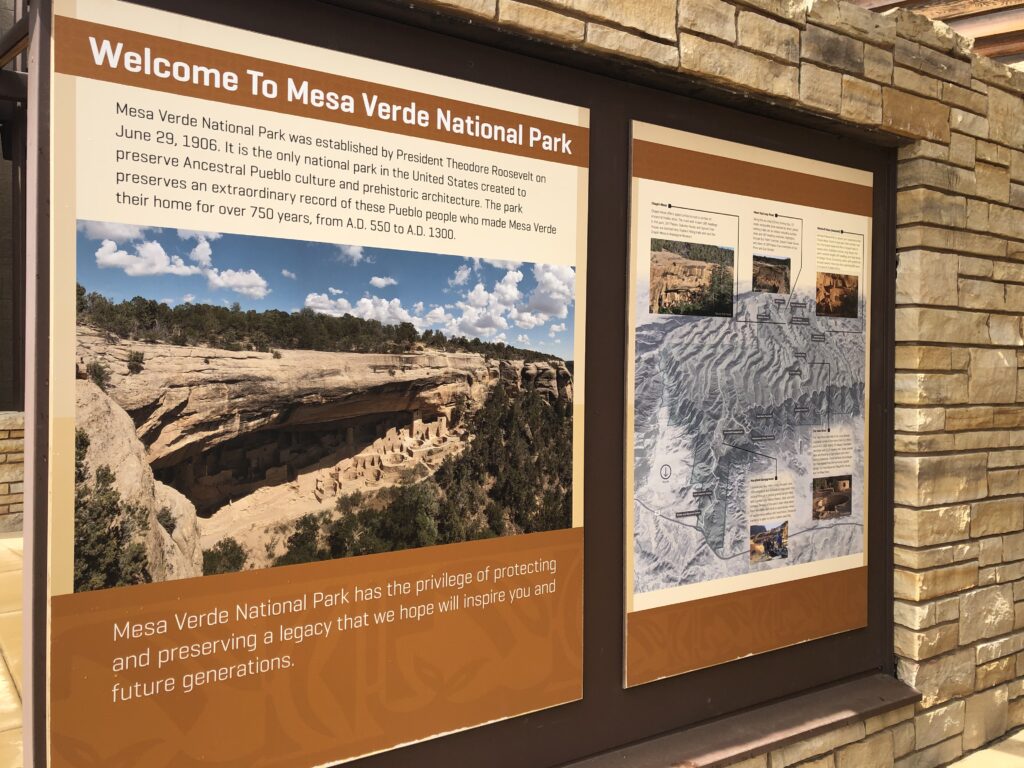

Mesa Verde National Park

Another one of Southwest Colorado’s jewels is Mesa Verde National Park. Located 35 miles west of Durango, the park offers a phenomenal opportunity to examine the lives of the Ancestral Pueblo people who made this area their home. Within this magnificent arena are nearly 5,000 known archaeological sites, including 600 cliff dwellings. These are some of the most notable and best-preserved sites on the continent.

Mesa Verde (Spanish for “green table”) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, so distinguished for its significant archaeological relevance. It is testament to the rich cultural traditions and history of Native American tribes in the American Southwest.

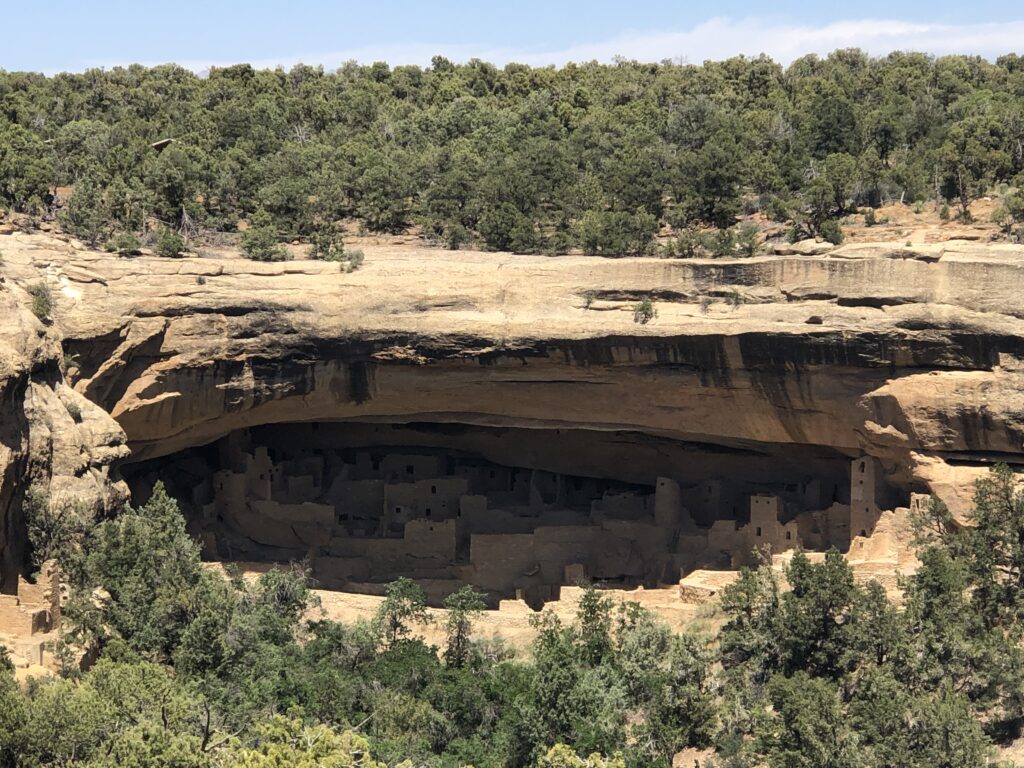

The cliff dwellings, which were built in the late 12th and 13th centuries, are truly remarkable constructions. Made of sandstone, mud mortar and wooden beams, they are tucked into the alcoves beneath overhanging cliffs in the steep-walled canyons. They range in size from one-room storage areas to complex villages of more than a hundred rooms. It’s mind boggling to consider how much labor was involved in the formation of these dwellings, and the continued repairs and remodeling necessary in their upkeep.

These homes speak powerfully of a people skilled at building, artistic in nature and adept at making a living from a land rife with challenges.

The most famous and largest of the dwellings is Cliff Palace, which boasts 150 individual rooms and more than twenty kivas (areas used solely for religious rituals). Studies reveal that approximately a hundred people lived here. It is also thought that Cliff Palace served as a social and administrative site, where special ceremonies were conducted.

As I looked at the doorways of this and other dwellings, I paused to consider the size of the people who once graced these premises. Supposedly, an average man was around 5’4” tall, while an average woman measured about 5 feet. Being a petite woman myself, I would have easily fit right in!

Spruce Tree House is another expansive cliff dwelling, containing 130 rooms and eight kivas, with a population that ranged from sixty to eighty people. It was first discovered in 1888 by two ranchers who happened upon it while searching for stray cattle. A Douglas Spruce was found growing from the front of the structure, which provided a means of entrance to the dwelling for the men, as well as an apropos name.

Balcony House, with forty rooms, is considered a “medium size” dwelling. It offers a good illustration of how room and passageway construction developed over the years.

The park also contains early pit houses (from AD 550 to 750), above ground pueblos and religious structures, which can be accessed via the six-mile Mesa Top Loop Drive. Check out the view at Sun Point. Visible from this spot are a dozen cliff dwellings set in the high reaches of the canyons, along with the unique mesa-top building called Sun Temple.

Mesa Verde was a thriving mecca and home to thousands of people until the late 1270s; at which time, the population then began migrating south into present-day New Mexico and Arizona. By 1300, Mesa Verde was deserted. Theories are offered to explain the migration, from drought and crop failures to animal depletion and social and political problems. Or perhaps, the people just wanted to find new opportunities elsewhere.

If you go:

Great Sand Dunes National Park: www.nps.gov/grsa

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park: www.nps.gov/blca

Mesa Verde National Park: www.nps.gov/meve