The famous and infamous of Lincoln County, NM

Some of the wildest history of the Wild West can be found in Lincoln County, New Mexico. Colorful characters like Billy the Kid, Sheriff Pat Garrett and even Smokey Bear resided in or passed through this area at one time or another.

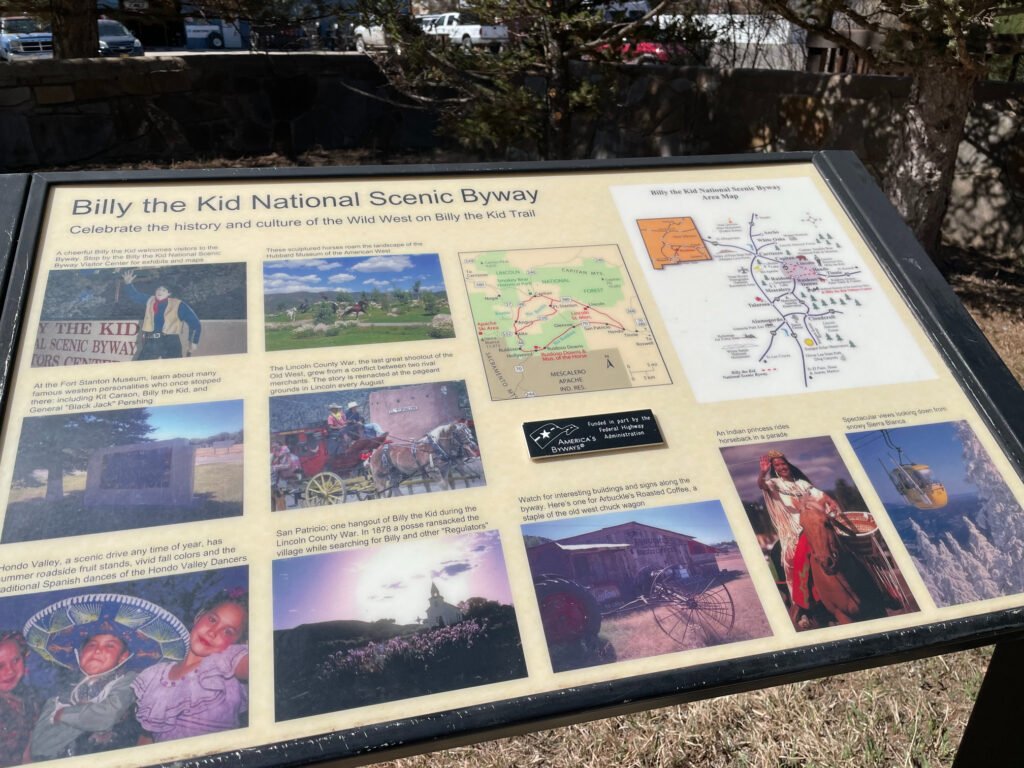

Travelers to the Land of Enchantment can take the Billy the Kid Scenic Byway for an opportunity to explore Lincoln County’s fascinating past. There are several historic sites, museums and parks along the way that will take you back to the years when New Mexico was a Territory and lawlessness abounded.

The Lincoln Historic Site is the most widely visited state monument in the state. The site is unique in that it manages most of the historical buildings in the community of Lincoln, a town made famous by one of the most volatile periods in New Mexico’s history.

This is a place frozen in time, with seventeen structures and outbuildings preserved as they were in the late 1800s. A number of them are open to the public. Begin at the Anderson-Freeman Visitor Center, where you can view the “Voices from the Past” exhibit for information about the region, pivotal players and significant events.

Story has it that the roots of the trouble in this county stemmed from a rivalry between lawyer and businessman Alexander McSween and merchant Lawrence Murphy. The two were at odds over cattle, as well as their respective mercantile pursuits. McSween wanted fair competition in the town, which was essentially under the steel hand of Murphy.

The town took sides with noted cattleman John Chisum joining McSween and his partner, John Tunstall, while Murphy and his second-hand man, James Dolan, had Sheriff William Brady and his deputies backing them.

Henry McCarty, a.k.a. William Bonney, a.k.a. the notorious Billy the Kid, was a tough, smart and charming young man. Orphaned at fourteen, he fell in with a rough crowd and became one of Chisum’s “Regulators,” a quasi-official law enforcement gang hired to protect McSween’s store. Murphy, on the other hand, hired the Jesse Evans Gang to do his bidding.

Murder and mayhem naturally ensued. After shooting Sheriff Brady, the Kid fled the county and newly elected Sheriff Garrett swore he’d capture and arrest him for Brady’s death. And he did. Billy was tried and sentenced to die, but before they could execute him, he escaped from jail and headed to the hills. Eventually, his luck ran out when Garrett tracked him to Ft. Sumpter and shot him.

That was the end of the Kid, but only the beginning of his massive popularity. Billy became a towering Wild West legend and over the years, more than sixty films were made of him, along with a slew of books and poems, and even a ballet.

Walking the streets of Lincoln today is the same as it was over a century ago. The spirit of the West is alive and well at this veritable time capsule. Stop in at the Montano Store, which was used as a stronghold during a memorable battle, or the John Tunstall Store, which originally housed a mercantile, law office and bank. There are still displays of the original 19th-century merchandise in the original shelving and cases.

At the Luna House, now the Lincoln Gallery of Western Art, enjoy a collection of western themed paintings and sculptures. The Convento was once operated as a saloon, then leased for use as a courthouse. Later it served as a Catholic chapel and a home for nuns who taught school in town. The Torreon, a circular castle keep-like building that’s hard to miss, was one of many defensive structures found in New Mexico back in the 1800s. There’s also the San Juan Mission Church, the town’s first permanent place of worship.

The Historic Lincoln County Courthouse is a favorite of visitors. It was first a general store and Murphy’s headquarters before becoming the town’s courthouse in 1881. It was from this building that the Kid made his famous escape, shooting and killing two deputies from the staircase and windows.

Private properties line the streets of the town, intermixed with those open to the public, and there are markers to indicate where certain events happened, like the location of where Sheriff’s Brady was ambushed and killed.

Fort Stanton, also a New Mexico State Monument, is another significant site along the Billy the Kid Scenic Byway. Set on 240 acres, the fort is comprised of 88 buildings, some dating back to 1855. Featured are officers’ quarters, barracks, a hospital, nurses’ quarters, morgue, dining hall, chapel, guardhouse, gym, pool, stables, fire station, and yes, a still functioning U.S. post office.

Start your self-guided tour at the Fort Stanton Museum, where you’ll find plenty of history about the fort’s early days and its segue well into the 20th century. After closure as an Army post, the place served a variety of purposes including a tuberculosis hospital, WWII internee camp, training school for the disabled and most recently as a low security women’s prison.

As you meander around the impressive grounds and in and out of the buildings, know that you are at one of the most intact 19th century military forts in the country. Of special interest is the hospital, with its medical equipment and informative displays explaining the medical theories and practices used to treat tuberculosis during that time.

The byway also leads to the village of Capitan, where you’ll discover Smokey Bear Historical Park and the burial site of the world’s most well-known and beloved bear.

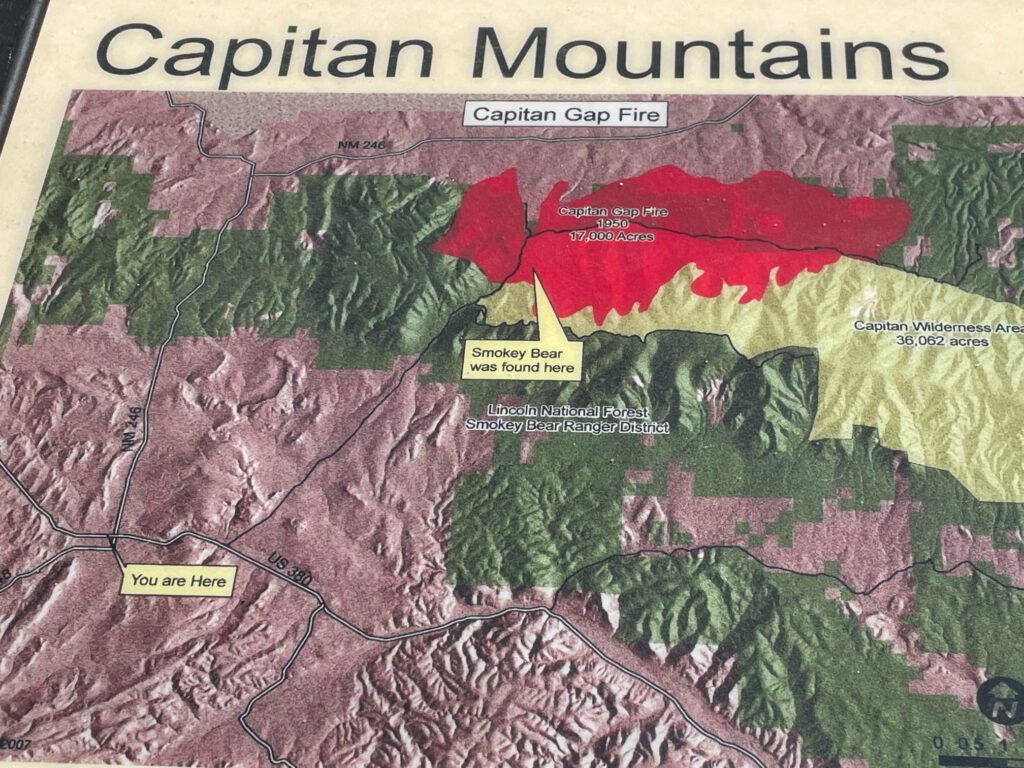

The tale of Smokey can be traced back to May 4, 1950, when a discarded cigarette butt started a mega blaze in the Lincoln National Forest. Two days later, a second fire ignited in the same area. Together these fires destroyed 17,000 acres of forest and grasslands. On May 8th, a crew found a badly burned bear cub clinging to the side of a tree. He was given the name “Hotfoot” initially, but that soon changed to Smokey Bear. Smokey received treatment at a vet hospital in Santa Fe and later went to live at the National Zoo in D.C., where millions of people visited him.

You might be surprised to learn that Smokey Bear was first an advertising campaign character conceived of in 1944 during WWII to raise awareness of national forests. After being found, the little cub officially became the living symbol of the fire prevention campaign and his picture graced billboards, signs, t-shirts and more. Upon his death in 1976, his body was returned to Capitan and buried in the small park that bears his name.

Smokey, believe it or not, is second in popularity only to Santa Claus. A brochure at the Smokey Bear Historical Park cites a study done of school kids in the U.S. and in selected countries around the world to determine awareness of familiar slogans and the ability to finish them when only the first few words were given. With “Only you,” more children were able to complete “Can prevent forest fires” than any other motto presented.

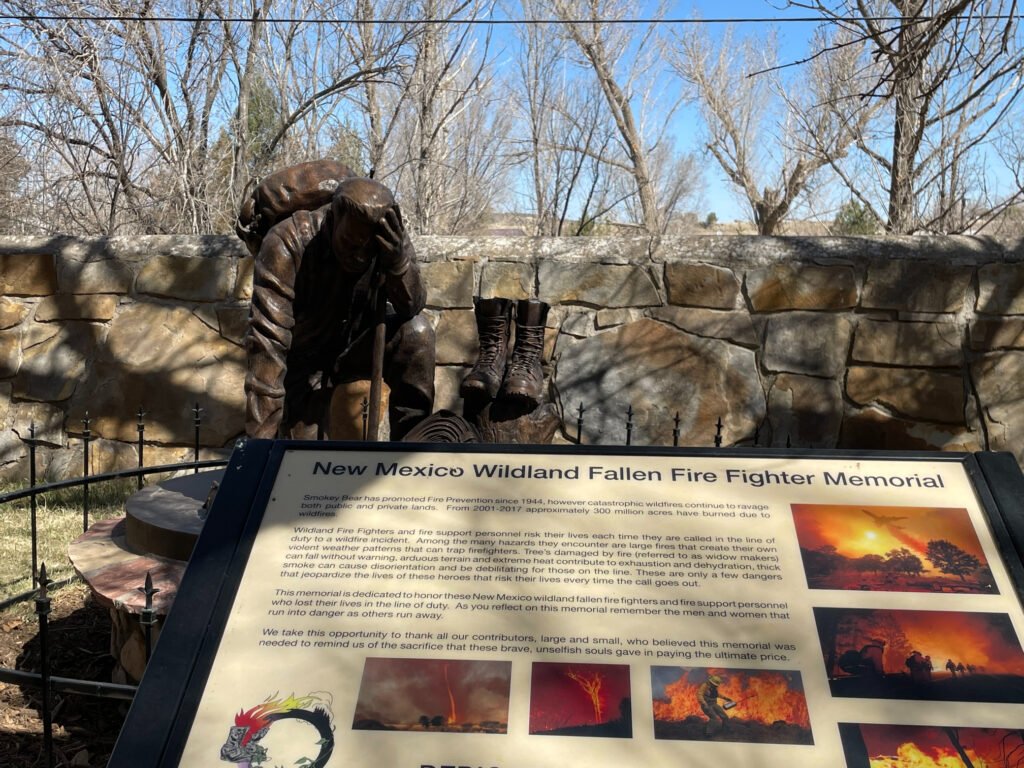

The park not only promotes Smokey’s fire prevention message, but also helps to draw attention to firefighters with a memorial dedicated to honor New Mexico wildland fallen fire personnel who lost their lives in the line of duty.

As you stroll around the 2-acre site, take the time to enjoy the numerous interpretive exhibits. They focus on the different vegetative life zones found in the state, from Chihuahuan Desert and Ponderosa Forest to Pinon/Juniper Grasslands and Sub Alpine Forests. And if you happen to visit in summer, I’m told the Butterfly Garden is a treat.

To learn more visit lincolncountynm.gov.