Realm of the Giant Pacific Octopus

“Below the thunders of the upper deep,

Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth…”(excerpt from The Kraken, by Lord Alfred Tennyson)

“Supple as leather, tough as steel, cold as night!” was how Victor Hugo described the writhing tentacles of a giant octopus in his 1866 novel, Les Travailleurs de la Mer. Hugo wrote of an unimaginable account of a man embroiled in a life or death struggle with a malevolent blood-thirsty cephalopod. Indeed, what could be more horrible than to find oneself suddenly trapped in a nightmarish death struggle with a slippery, eight-armed sea monster?

Octopus Dolfleini

In modern times, Hollywood filmmakers have propagated the octopus’s celebrity by portraying them in B movies as villainous creatures that either terrorize seaside communities, prey on unsuspecting treasure divers, or drag ill-fated ships to the bottom of the sea. Fortunately for mankind, these dramatic myths are based more upon fiction, than fact. Of the more than 289 species of octopus in the world there is only one that can truly be called a giant – the giant Pacific octopus (octopus dolfleini), the largest octopus in the world. These behemoth cephalopods inhabit the cold coastal waters of the North Pacific Ocean from Japan to California from the shoreline to depths of 183 meters (600 feet). Though population estimates don’t exist, the species is not deemed to be an endangered species. Supremely intelligent, these brainy octopus are known to solve mazes very quickly and unscrew jar lids to retrieve food inside the jar. They are also one of the only marine invertebrates that actually employ strategy, rather than instinct, to capture their prey.

Beguiling Cephalopods

The largest giant Pacific octopus ever found reportedly weighed 600 pounds and measured 31 feet (9.5 meters) from tentacle to tentacle. Though disproportionately strong for their size, as demonstrated by one enterprising 40-pound octopus at the Seattle Aquarium who once escaped after moving a 60-pound weight from the top of its tank, giant Pacific octopus need not be feared. In the wild, they have proven themselves to be shy, intelligent, gentle and harmless creatures. West Coast scuba divers consider an encounter with these beguiling cephalopods to be the highlight of any dive. While they might be giants, Pacific Northwest underwater photographers salivate at the very thought of capturing just one photograph of their dive buddy seemingly entangled in the gripping embrace with Hugo’s fictitious sea monster. In reality, there is nothing death defying about these images as octopus are non-aggressive creatures.

Like many other ocean predators, octopus hunt their prey by night, habitually retreating to their dens during the daytime hours which can be either under a rock, squeezed into a natural rock crevice, shipwrecks or underground caves. Apart from providing some protection from its predators, their den is also used for hatching their eggs, or feeding. A telltale sign that marks the entrance to an octopus’s den is a pile of shells and other rubble that the octopus has discarded. Like most cephalopods, the giant Pacific octopus has a brief life span of only three to five years.

Three Hearts, Nine Brains, & Blue Blood?

Giant Pacific octopus are about 90 percent soft-bodied muscle except for two small plates anchoring their heads, together with a beak used to grasp and bite prey They possess three hearts and nine brains. Two smaller hearts pump their blue blood to the gills, while a larger third heart circulates blood to the rest of the body. One central brain controls their nervous system and there is a large ganglion of nerve cells at the base of each of their eight arms, which act like independent brains that work both independently and together to coordinate movement. Their blue blood contains a copper-rich protein called hemocyanin which is more efficient than hemoglobin in cold ocean environments and improves oxygen flow.

The Eyes Have It!

All octopus have highly advanced eye structures which contain many of the same parts human eyes do, including: the iris, the pupil, the lens, the retina, and the optic nerve. However, an octopus pupil is not a round shape, but a horizontal slit. To focus, the octopus’s eye moves the lens forward and backward, instead of altering its curvature like human eyes do. For octopus, the eyes are one of their most important senses. Octopus possess a complex system of specialized pigment sacs called chromatophores, nerves and muscles which they utilize to change color and texture to camouflage themselves and blend in with their environment. Octopus also produce a toxic ink which is stored in large glandular sacs.

Aquatic Escape Artists

Whenever an octopus feels alarmed, it squirts a cloud of ink to distract and confuse the potential threat, while simultaneously propelling itself in the opposite direction to escape. Despite this defensive maneuver, octopus frequently lose an arm to predators which fortunately will grow back. However, male octopus take extra care to protect its third arm which has no suckers along the last few inches. Indeed, this is an appendage worth saving as it is used for mating when it’s inserted into the female’s body cavity.

Eight Arms & 280 Suckers to Hold You!

Finding a giant Pacific octopus is relatively easy at many select dive sites in British Columbia. One site in particular that always seems to deliver is Argonaut Wharf in Campbell River. Situated at Tyee Spit, the wharf is accessed either by shore entry or dive boat. Our preference has always been to make a splash along the wharf’s outer pilings.

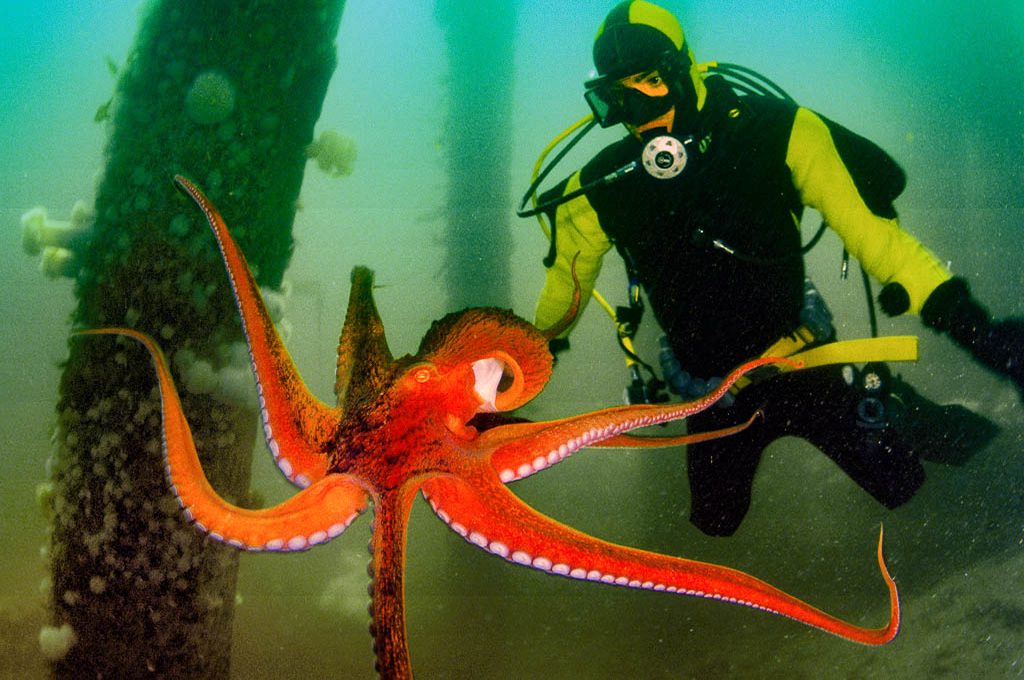

From the surface, Argonaut Wharf appears to be an unlikely spot for a dive site, let alone be considered an octopuses’ garden. Yet, over the years this undersea cathedral has proven to be one of the Pacific Northwest’s best places to find giant Pacific octopus. Its shallow sandy bottom begins in about 10 feet of water and slopes gradually to a depth of about 40 feet toward the Discovery Passage’s inviting current-swept channel. Since we needed some portraits of a diver interacting with the world’s largest octopus, Argonaut Wharf seemed to me to be a good place to start.

Some diving days you get lucky. And this one proved to be no exception. Before I had even reached the sea floor thirty feet down, I could see that one of my diving partners had already found a giant Pacific octopus out in the open, clinging to the side of a wharf piling. Not too shabby, I thought, since he only had a two-minute head start on me. I framed the scene in my camera’s viewfinder and commenced making pictures.

The photo opportunities during this dive were tremendous. We watched with glee as this mesmerizing eight-armed creature propelled itself skyward, and then descended like a rubbery parachute towards the sand. Then, as if signaling the end of our meeting, the octopus seemingly tried to melt into the background by again clinging to one of the piers supports pilings with its suckers. Clearly, Argonaut Wharf is one of those unlikely dive sites that continues to shine as a place where luck happens.

An Octopus’s Garden

Another sure-fire dive site for encounters with octopus is Dillon Rock, which is situated at the mouth of Shushartie Bay, off the northern tip of Vancouver Island. A green navigation marker pinpoints the top Dillon Rock making it very easy to find. What looks small and unassuming on the surface gives way to something more inviting beneath the waves. Dillon Rock slopes gently down for about 15 or 20 feet underwater before you hit a vertical wall that drops more steeply to sand and silt bottom at approximately 80 feet. A lush forest of bull kelp crowns the top 30 feet of the rock thus providing shelter for a multitude of schooling fish. Dillon Rock can be circumnavigated quite easily during one dive. Visibility can vary from day to day so I suggest carrying a light to search the rock’s nooks and crannies.

It is not uncommon to see as many as a dozen friendly wolf eels and potentially half as many large octopuses on one dive. Though octopus tend to hide out in the cracks and crevices that they use as their dens, you are more likely come across one sitting right out in the open than anywhere else. They seem to have grown accustomed to the presence in their midst. The pristine emerald seas that surround Vancouver Island offers some of the best cold-water diving in the world. It is little wonder that many who have dived at Dillon Rock rate it as being one of their absolute favorites. In these northern seas, Dillon Rock is one of those amazing dive sites that deliver wolf eels and octopus on just about every dive.

It is not uncommon to see as many as a dozen friendly wolf eels and potentially half as many large octopuses on one dive. Though octopus tend to hide out in the cracks and crevices that they use as their dens, you are more likely come across one sitting right out in the open than anywhere else. They seem to have grown accustomed to the presence in their midst. The pristine emerald seas that surround Vancouver Island offers some of the best cold-water diving in the world. It is little wonder that many who have dived at Dillon Rock rate it as being one of their absolute favorites. In these northern seas, Dillon Rock is one of those amazing dive sites that deliver wolf eels and octopus on just about every dive.

During my first of two descents at Dillon Rock, I discovered a large octopus sitting out in open among the broad amber colored leaves of bottom kelp. Unfortunately, my camera was only equipped with a macro lens so I could not shoot any wide-angle pictures. Approximately 4 hours later, I returned with my wide-angle camera rig to the precise location where I had last seen my octopus. Amazingly, I found him in the exact same place approximately 4 hours later. While I focused my attention on this one octopus, other divers emerged from the water claiming that they had seen as many as five different octopuses on their dive.

The Kraken Sleepeth

Truth is stranger than fiction. Giant Pacific octopus are not the nightmarish sea creature Victor Hugo described in his famous novel. Nor can this amazing cephalopod be compared to a horrifying sea monster like the mythical Kraken who wraps their eight writhing tentacles around the hulls of ships, crushes them, then drags them down to Davy Jones’ Locker. In reality, the giant Pacific octopus is one of the signature marine species in the Pacific Northwest’s Emerald Sea. Amazing encounters await undersea explorers who dive… “Below the thunders of the upper deep. Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea. His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep. The Kraken sleepeth… in the realm of the giant Pacific Octopus.”

Until our next dispatch, dare to Explore… Dream… Discover.

British Columbia Dive Operators

While no marine life encounter is 100% guaranteed, the following BC Dive Operators can take you to places where you are more likely to encounter Giant Pacific Octopus:

Browning Pass HideAway Resort: https://vancouverislanddive.com/

Stongwater Retreat: http://www.porpoisebaycharters.com/new_page_1.htm

Rendezvous Dive Adventures: www.rendezvousdiving.com

Sundown Diving: http://www.sundowndiving.com/

Abyssal Dive Charters & Lodge: http://www.abyssal.com/home.html

Pacific Pro Dive and Marine Adventures: http://pacificprodive.com/

UB Diving: https://www.ubdiving.

Expedition Svalbard 2019 with Jett & Kathryn Britnell

“Interested in stories about underwater photography and protection of our oceans’? What are you doing 14-24 August this year? I am so pleased to say that our friends across the sea, both fellows of the explorer’s club and much much more, are joining us on board the M/S Quest these dates! Come join Jett Britnell, Kathryn Britnell and PolarQuest to the realm of the Polar Bear, the haven for Walrus and the beautiful landscape of Svalbard!”

~ Marie Lannborn Barker, CEO, PolarQuest